Strategy and innovation strategy are hard to separate. Here is what happened when I finally managed to do it and learned to map!

Strategy and innovation have become increasingly intertwined (see, for instance, https://www.strategy-business.com/article/00239?gko=8e54d). It is a common meme repeated across industries for a long time. But what does this intermixing of strategy and innovation mean? And how is innovation strategy so important all of a sudden? And was innovation not a factor in the good old days? And what is the difference between a strategy and an innovation strategy anyway?

In this article, I will go through my journey in strategy land. The journey's outcome was me finding a way to redefine innovation strategy for myself, which has led to a quantum leap in finding promising areas of innovation. This way of thinking has created a new mental model for me, I hope it can do the same for you.

The painful beginning of a journey in strategy discovery

In a public speaking engagement I held on innovation strategy, an audience member asked a leading question. The question was whether “strategy is dead now, innovation strategy is taking over everything”. I said something along the lines of “yes, it is for sure taking over” and agreed with the audience member, but I honestly did not know the answer. Is strategy not important anymore? Where do we draw the line between a strategy and an innovation strategy? Is that line being erased? Did it ever exist? I felt like a fraud for agreeing with the audience member without knowing the answer. I had reached a point where I had to educate myself to keep talking about the subjects close to my heart.

With a clear purpose, I set out on a mission to understand the difference between an innovation strategy and a “general” organization strategy. With that understanding, I hoped to answer why innovation strategy has become so important. Alternatively, I would like to know if innovation strategy is just a buzzword. Since I didn’t exactly know what a general strategy was (shame on me), I had to start by understanding that. Don’t get me wrong, I roughly knew what a strategy was, and I knew that the outcome was (most of the time) several strategic initiatives or focus areas. I think my level of knowledge at the time and my situation are recognizable to many people across the board. Many of the large clients I have worked with have identified 5-7 areas where they want to focus their work. But how you get there and motivate your choices were not clear to me, and most of the time, not clear to people inside the organizations either.

Why is strategy, as traditionally taught, so unsatisfying?

The strategic frameworks and the strategies I had seen and developed never really had an answer to “how to win”. I felt that in most cases, you just gather a lot of data and hope that the data will tell you what to do. That intuition will strike. The ad hoc approach to finding ways to win didn’t strike me as something that would actually give us ways to win in most cases. And this fact showed in the strategies I had been a part of developing as a consultant. We would find interesting activities, but what pointed to them being correct? The dubious chance to wind due to the strategy also reflected my experience as an employee in large organizations. The strategy was some direction, but I had never found out why the people in charge chose those specific directions and WHY they would provide the way to win.

Different schools of thought describe generic ways and give mental models for ways to win but do not help that much in a situation where a strategy is needed. In a way, the knowledge from many strategic frameworks helps to classify activities after the fact. Which is not useful other than for post-mortems.

Striking gold, the solution to strategy woes

With the introduction of Simon Wardley’s frameworks for strategy, a connection, and distinction between strategy and innovation strategy finally became apparent to me. Based on the strategy cycle and value chain maturity maps Simon has developed, it becomes relatively easy to make the connections and ultimately visualize where the innovation strategy follows from the overall strategy. Once I read Simon’s book, almost everything about strategy was in place. It finally gave me an answer to why strategy had been such a confusing subject to me before. With Simons's help, I now have a toolbox to make and motivate strategic choices. I have also gained a much broader understanding of the role of innovation in the overall strategy.

The implications for innovation strategy and innovation management from Simon’s work are several. I will try to elaborate on some of the impacts here and how the repercussions change existing approaches that we know from innovation management.

For the sake of making a free-standing understandable story, I will provide an introduction to Wardley mapping and the strategy cycle. They can be read and understood better and more in-depth by reading other people’s materials, especially Simon’s book. There is an intense ecosystem around Wardley maps, and what is described here is only just scratching the surface.

The strategy cycle

The strategy cycle is Steven’s take on Sun Tzu's principles for competition combined with the OODA loop developed by John Boyd. The cycle consists of five parts:

Purpose, Landscape, Climate, Doctrine, and Leadership. (The OODA loop is Observe, Orient, Decide, Act)

Simon Wardley’s strategy cycle: Sun Tzu, John Boyd and the two Why’s

Purpose: Why are we doing what we are doing?

Landscape: Where is it that we are going to compete? We need a map to understand what the landscape looks like.

Climate: How are the individual parts of the landscape affected over time? What are typical patterns of how things move and change?

Doctrine: General principles that are useful to win the game we are playing. What do we train our people to do? Closely related to capabilities.

Leadership: Given our landscape, climate, and doctrine, what choices and plans will we make to beat our competitors and win in the market? We implement and then start the strategy cycle all over again.

Landscape, reading the Wardley map

Simon makes the very valid point that military strategy relies heavily on maps. We also would have difficulties playing chess if we did not know what the chessboard looked like. All valid points. So how do you develop a map for business? You combine two phenomena: The value stream and the evolution curve (similar but not the same as diffusion curves for technology adoption).

Wardley map of a tea shop. Source Simon Wardley

By first understanding the value stream and anchoring the value stream in the user's needs we understand how an organization delivers value to the customer. To understand movement and maturity in the value stream as parts of the value stream become more mature, we add a maturity axis to know how evolved the different components of the value chain are. The chain and the state of evolution becomes our map of the competitive landscape. Our Wardley Map.

In this example, we see that our value chain has relatively mature components, but our kettle is custom-made for some reason. It is likely better from an economic standpoint to have a standardized kettle. We would standardize unless this kettle has some unknown effect on our tea that helps us win. Knowing that the kettle is seen as custom-made gives us a chance to challenge the map, which is another piece of the puzzle as to why Wardley maps are such useful strategic tools.

Climate, what are the patterns for how components in the map move (that we have no choice over)?

There are a large number of climatic patterns defined by Simon. Climatic patterns are things that effects us that we have no choice over. One of the most important ones is the fact that everything evolves. All components tend to move from immature to mature, from custom-made to commodity. The evolution follows from competition in the marketplace. Another climatic pattern is that a component that matures, especially when becoming a commodity or utility, enables new components to be built that consume this new utility.

An example is electricity which became a utility with a standard interface. With a standard interface, creating lights, radios, and refrigerators becomes easier. You no longer need to build a generator yourself or bundle a generator with your lightbulbs.

Kettles are evolving to a commodity. In our teashop we have inertia that is resisting the change..

These two processes describe what Joseph Schumpeter called “creative destruction,” where the value of something is diminished over time by entrepreneurial competition and new innovation is based on the more accessible components that innovation and competition creates.

A third climatic pattern is that successful organizations build inertia. If you have successfully competed using a component in a particular state (for instance, a product), you will have internal resistance against turning this component into a commodity utility. And you will have inertia against switching to a commoditized version if you use a product.

Several other climatic patterns have effects on how things develop, and they can all be described using the map. The map gives us a visual way to anticipate events, actions, and behaviors.

Doctrine, what are things we do that are universally applicable

The doctrine has a profound effect on an organization's ability to make strategic changes.

I will elaborate on doctrine later in some other article. Simon has a list of generally applicable doctrines which may or may not apply to you or your competition. Doctrine in a business setting is simply some generally useful patterns that lead to an improved understanding of our situation and, in the long run, to more robust business performance. People from the Wardley mapping community and Simon himself have divided the doctrine patterns into four phases. Shown here is the first. The entire doctrine list can be viewed here: https://learnwardleymapping.com/doctrine/

Phase 1: Stop Self-Destructive Behavior

Communication

Use a common language (necessary for collaboration)

Challenge assumptions (speak up and question)

Focus on high situational awareness (understand what is being considered)

Development

Know your users (e.g. customers, shareholders, regulators, staff)

Focus on user needs

Remove bias and duplication

Use appropriate methods (e.g. agile vs lean vs six sigma)

Learning

Use a systematic mechanism of learning (a bias towards data)

Operations

Think small (as in know the details)

Leadership, what moves do we make

Now that you know the landscape, climate, and doctrine, you can start to create gameplays that you believe will help you win. There are advanced patterns here too, but in most cases, it is enough with a simple understanding for the relatively immature organization to generate good strategic moves. For instance, removing custom-made components far from the end user in the value chain.

What does the newfound knowledge mean for Innovation strategy?

Loosely defined, your strategy determines the actions you believe you need to take to win. In the area where you have decided to play. (note, there are several definitions of what a strategy is, this is one)

If that is the definition of strategy, the innovation strategy should determine what innovations you want to explore to win with your strategy. If true, you have a coherent innovation strategy supporting your business goals. That is, you innovate in line with what your strategy tells you to explore.

Innovation strategy then becomes a collection of choices. The choices or activities consist of a mix of possible actions we can describe through maps:

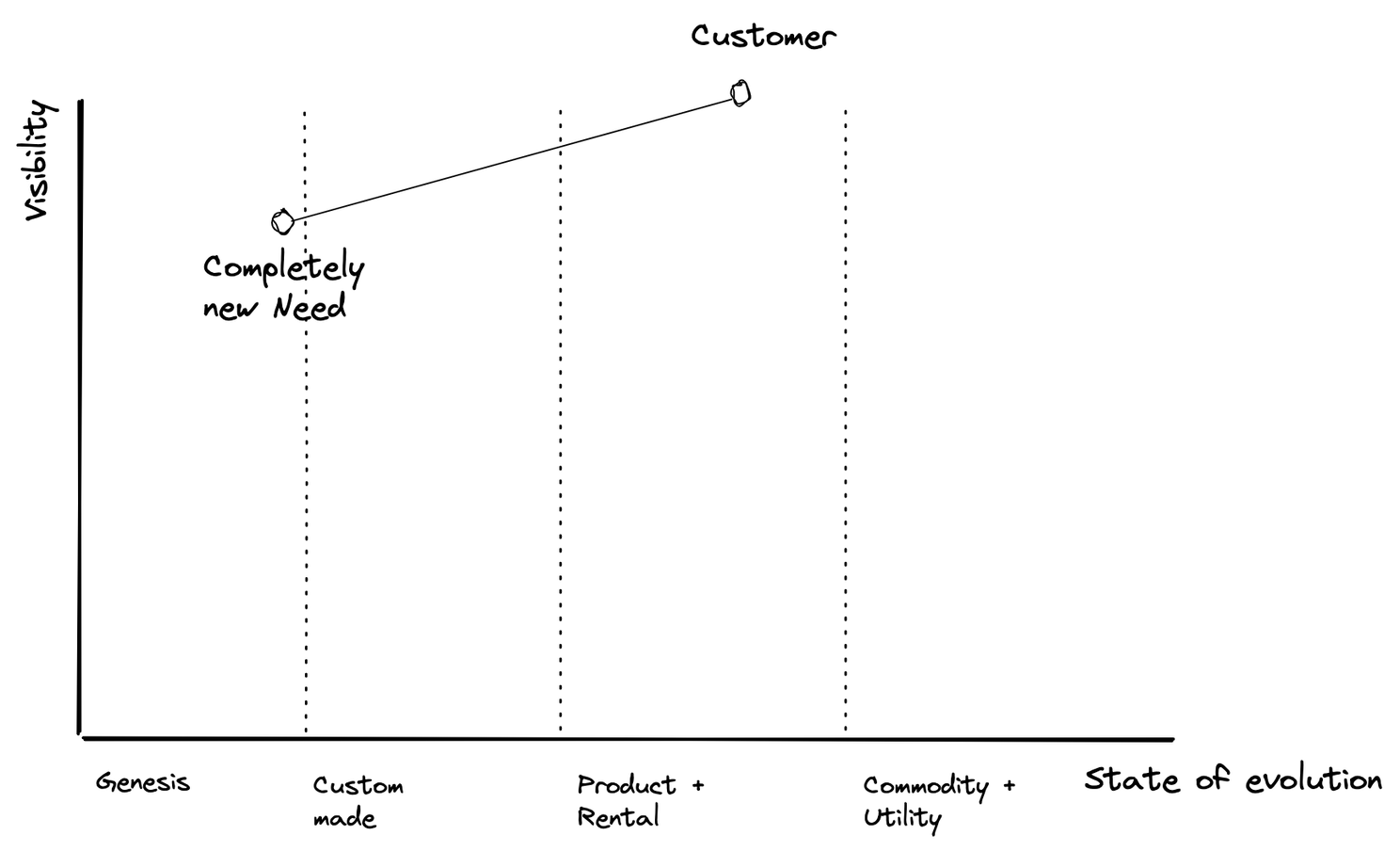

1. Identify and serve (entirely) new emerging customer needs (“external” innovation)

2. The creation of improved or substitute solutions to servicing existing customer needs (“external innovation”)

3. Creating a more effective value chain (removing or changing parts of the value chain, “internal innovation”)

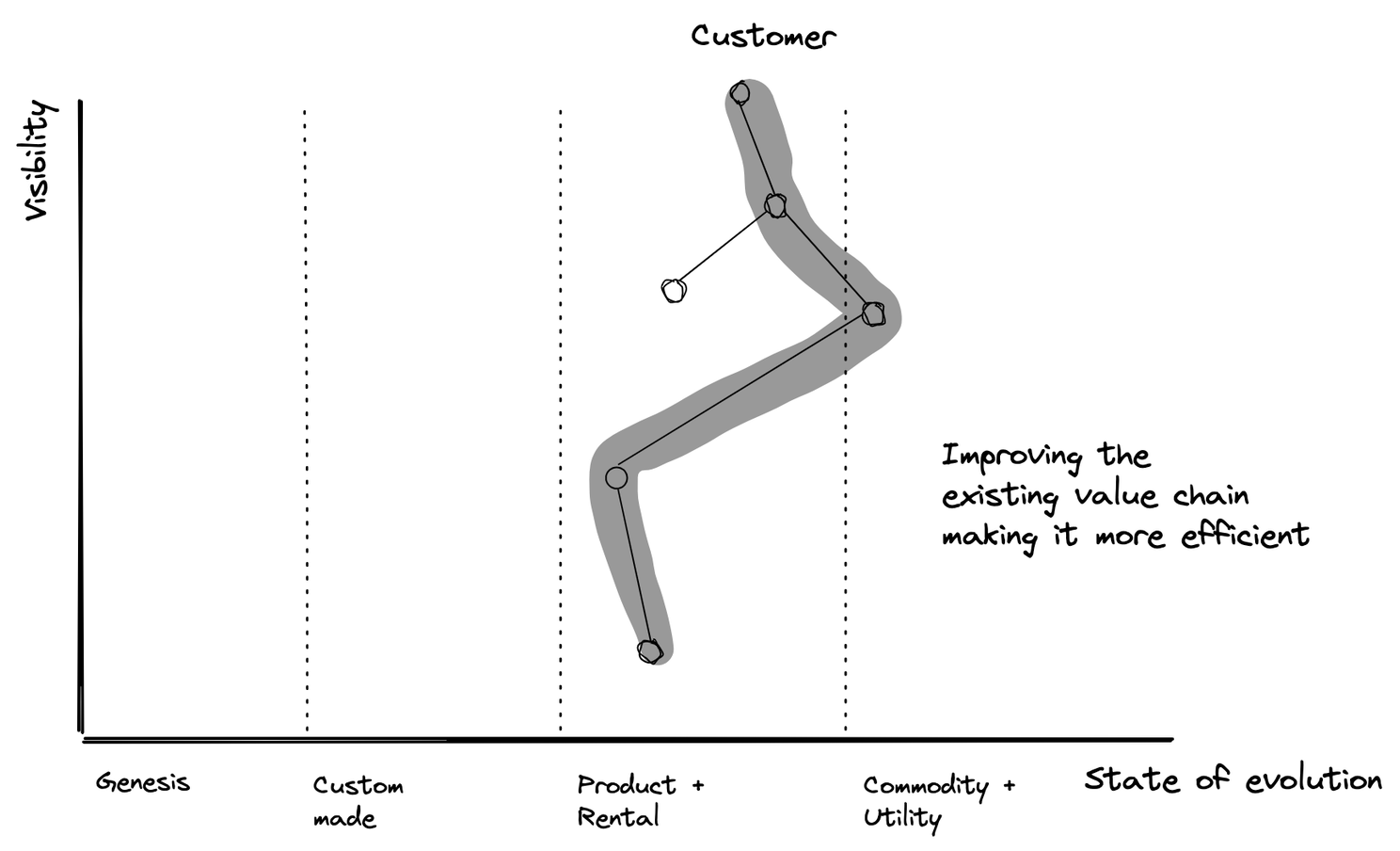

4. Creating a more efficient value chain (improving the existing value chain, “internal innovation”)

Note that changing the value chain can include changing ways of working. For instance, changing to agile practices or DevOps. It can also mean changing the organizational structure, for example, going from siloed departments to cross-functional teams.

The key is we are making these changes to respond to some sort of challenge, not for their own sake.

The commoditization of products and services follows from the competition in the market. To overcome and win against the competition, we innovate using the four types of innovation. Inertia is a blocker to the innovation becoming accepted. Especially at boundaries between phases (custom made -> product-> utility).

Note: For innovation management professionals, this is a generalization and a higher level of abstraction for the forms of innovation we usually talk about. You can describe for instance, “the ten types of innovation” using a combination of these at a higher level of abstraction.

What does this new definition of innovation look like if we place it on a Wardley map?

The identification and servicing of (entirely) new emerging customer needs.

When thinking about innovation, most people think of finding and serving new customer needs through products and services. Finding new customer needs is the realm of many startups, especially startups that have a new, previously untested technology as a base. Approaches such as lean startup are used to uncover what the customers actually want and respond to in this domain.

2. The creation of substitute solutions to servicing existing customer needs.

With needs already existing and identified, we come into more traditional product and service development. We are trying to improve the experience for an identified need. Cheaper, faster, better, less risky. Entering a new but known market is another example.

3. Creating a more effective value chain.

Changing the value chain to something new is a form of transformation. Changing to digital components is an obvious example. Removing manual steps or removing dependence on old technology is another.

4. Creating a more efficient value chain.

Improvements to the value chain are perhaps the most incremental type of innovation. This is where we take the existing components of the value chain and make them more effective or efficient. Make them cost less to run through some form of optimization or outsourcing.

Why does it matter?

While searching for the difference between innovation strategy and strategy, I often reflected on whether this is a question that matters. My conclusion was always that it does matter. Innovation is a very big word. Attempts to instill systematic innovation activities on a broad base outside of the incremental product, service, and process development often fail. The fact that we often fail means that the strategies for doing so are poor. If we get a transparent mental model for strategies and innovation strategies, we can better have broad innovation attempts work out.

Innovation strategy before Wardley is often expressed in terms of activities for growth in horizons (McKinsey) or activities spread in a risk matrix where the innovation can be “Core,” “Adjacent,” or “Transformational”. The idea is that a company should distribute its innovation risk and have a portfolio approach to innovation strategy.

A classic risk matrix, see for instance publications from George S Day.

For an organization that has gained situational awareness (through maps), we can no longer divide the innovation strategy into the three suggested alternatives in any straightforward way. The gameplay must determine how you as an organization approach innovation and create new value. However, the organization's capability for innovation activities must determine the gameplay, so there is a need to understand the doctrine for innovation activities.

In general, Simon Wardley suggests strategic gameplay that removes the need for riskier forms of innovation (especially in the origin phase). Customer needs are essentially unknown at this stage and will cost a lot of resources to capture. When an organization can identify early upcoming exploratory needs, it can be a vital source of competitive advantage. But going after early needs may also be a costly strategy. A strategy that could provide a proving ground for fast-following competitors to move in. Maps give us a way to describe these situations and understand them faster than most other approaches would.

Perhaps the most exciting thing is that Wardley maps often allow radical innovation through combinations or building on top of mature technologies. Lower execution risk and more significant results. That being said, nothing is ever a sure thing.

What have we done with the newfound knowledge?

The new insight around how we can describe innovation has led us (Rhubarbs) to adopt Wardley mapping into our approaches to innovation management. We have used it as a starting point for design thinking projects, product portfolio management, and several other applications. The results have been, for lack of a better word, extraordinary. The insights gained with the new level of abstraction that Wardley maps provide allow us to bring much better recommendations to our clients and bring those recommendations much faster. The best thing is that the maps give us a clearer picture of what it will take to win. With maps, we finally deliver what we believe is the best possible advice available every time.